Human-Centric sustainability marketing to drive consumer demand

Synopsis

Many hospitality brands communicate sustainable initiatives in generic ways that are not consistent or meaningful enough to attract additional consumers, and in some cases, may even cause reduced demand or backlash. A study of Swiss consumers found that for effective sustainable marketing, hospitality brands need to pay specific attention to three things: their sustainable initiatives should be specific enough to answer the targeted needs for a large portion of their consumers, they need to be communicated in a way that drives consumer action, and they should not incite dislike, annoyance or criticism from consumers.

Despite sustainable goals being on everyone's lips – nowhere more so than in the hospitality sector – it’s important to understand that sustainability doesn’t mean the same thing to all consumers. Differing consumer definitions of sustainability make it difficult for hospitality brands to respond to this need for sustainable practices.

Indeed, we regularly observe hospitality brands communicate sustainable initiatives in ways that are too generic. They might add a sustainable label to their advertising or might communicate their “greenness” in just one or two areas of their services. These strategies are not consistent or meaningful enough to draw additional consumers to their offerings. In the worst case, these actions may even cause reduced demand or consumer backlash.

The results of a study conducted on a representative sample of more than 650 Swiss consumers provide in-depth findings to better understand these differing perceptions.

3 key steps to effective sustainable marketing

Our research finds that hospitality brands need to pay specific attention to three things when engaging in sustainable marketing:

- First, their sustainable initiatives should be specific enough to answer the targeted needs for sustainability for a large portion of their consumers. Our research reveals that there are only two specific sustainable benefits: “connection to nature” and “connection to local region” that consumers are really looking for.

- Second, sustainability initiatives need to be communicated in a way that drives consumer action. At the present time, very few sustainable benefits actually convince consumers to spend money.

- Last, sustainability marketing efforts should not incense consumers, i.e., cause dislike, annoyance or criticism towards the measures – which currently, and surprisingly, is the case with more than 40% of the market!

Understanding the sustainability persona type

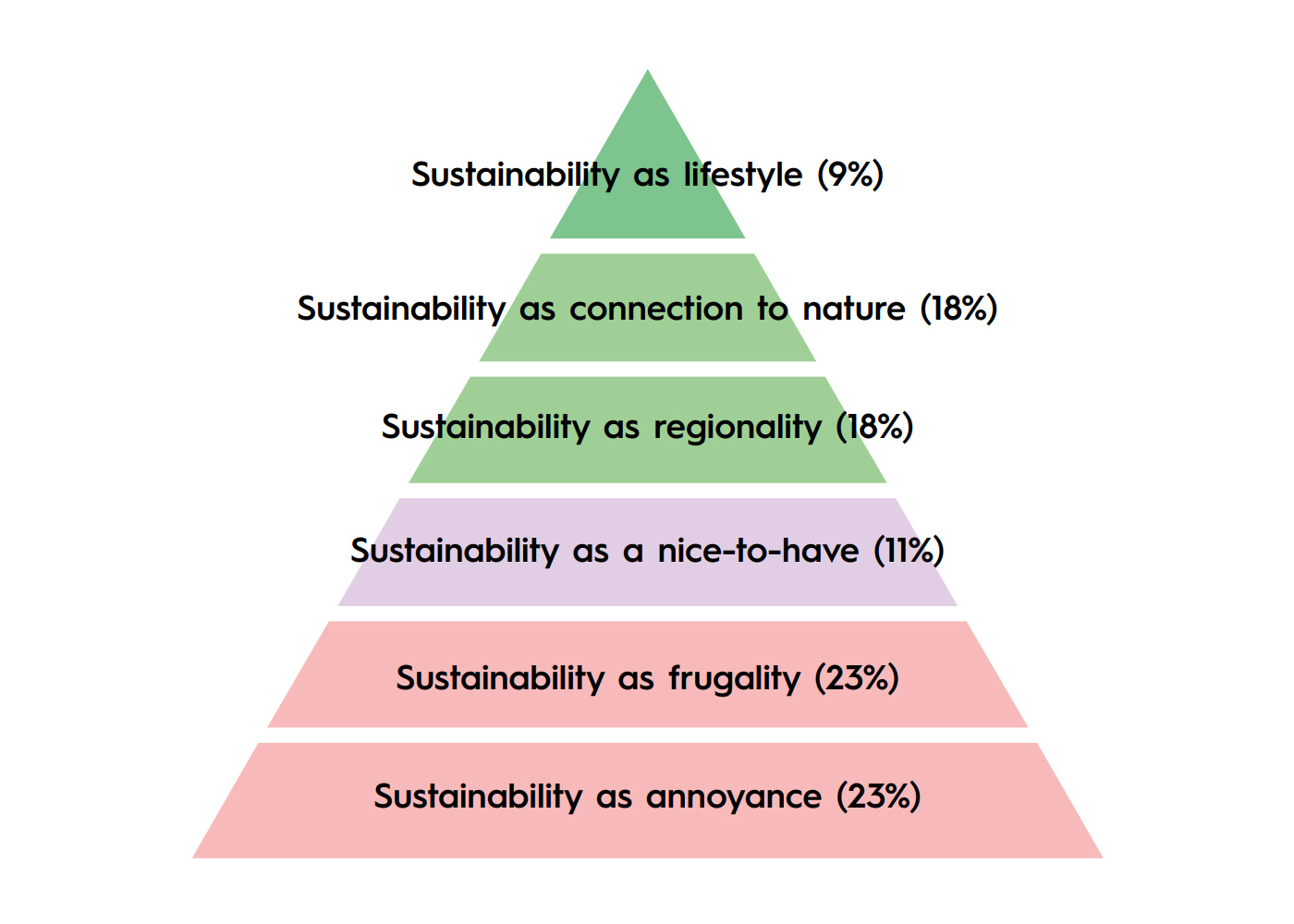

Reminiscent of the levels of Maslow’s pyramid of needs, consumers surveyed during our study were arranged by their affinity towards sustainability practices. When tackling sustainable initiatives, businesses should fully understand (and harness) the behaviors associated with sustainability in their market.

Sustainability-positive consumers

- “Sustainability as a lifestyle” (9% of the surveyed population): they believe everything needs to be sustainable and behave ‘sustainably’ in most areas of life. While all sustainability initiatives might appeal to this group, this group is small and might behave as “too sustainable” for mainstream businesses.

- “Sustainability benefits seekers”: they behave sustainably to be closer to nature (18%) or to be closer to the region they inhabit (18%). These groups think sustainability is positive, but are looking for specific definitions of sustainability. Businesses that wish to be considered by these consumers must provide offers suiting this definition of sustainability.

Sustainability-neutral or -negative consumers

- “Sustainability as nice-to-have” (9% of the surveyed population): consumers who would never buy or do something for the sole reason of being sustainable. Admittedly, sustainability is not a negative for them, but nor is it the main driver to their purchase decision-making process.

- “Sustainability as frugality” (23%) and “sustainability as an annoyance” (23%): the biggest groups by far are, sadly, those who think critically and negatively about sustainability.

- Consumers in the “sustainability as frugality” group dislike sustainability because they believe it will make everything more expensive. This is by far the poorest group in the sample, and the world moving toward sustainability means that many of their previous consumption patterns might become too expensive for them (e.g., they might not be able to fly on holiday because of new CO2 taxes on flight tickets).

- The second sustainability-negative group dislikes sustainability for more ideological reasons (“sustainability as an annoyance”). They fear that the move towards sustainability will result in removing their life’s pleasures, e.g., governments forbidding the consumption of meat.

What does this mean for hospitality brands?

These findings have fundamental implications for hospitality brands that wish to position themselves on sustainability. Mainly, these brands have two strategies at their disposal. Which strategy they can or should pursue depends on the sustainable benefits they offer.

- If a hospitality brand can provide sustainable benefits in the area of "connection to nature" and/or "regionality," it can use them in its pre-purchase marketing to attract a sizeable portion of guests wishing to behave sustainably.

- If a hospitality brand cannot communicate sustainable benefits in this area or can only communicate vague sustainable benefits, it should not try to take a sustainable positioning in its pre-purchase marketing. Such positioning would be weak compared to the competition and would only motivate a small group of guests.. Rather, the brand should use these benefits in post-purchase communication to reassure smaller consumer groups.

For example, the successful sustainable positioning of Costa Rica tourism is because it directly builds on the clear sustainable benefit for guests’ connection to nature. This is a strong positioning because this specific definition of sustainability resonates with many consumers.

In other cases, hospitality brands have realized that their sustainability offerings will not suffice for a sustainable pre-purchase positioning. However, it can still be used to reassure guests about their choices, such as the now ubiquitous example of asking consumers to reuse towels in a hotel.

Therefore, a robust and sustainable positioning can work depending on the benefits that a brand can offer and how they are communicated. In today’s information-heavy (‘rabbit-hole) society, hospitality brands need to be careful and selective about how their message is conveyed.

The communicated key sustainable benefits should focus on enabling the consumers’ closer connections to nature or the local region. Everything else will do little to attract consumers and might even drive consumers away from your hospitality brand’s offerings.

At a glance

What are the biggest sustainable marketing pitfalls?

What we see is that for a brand to be sustainable it has to be consistent all the way through. Sustainable – but only in part - doesn’t resonate with consumer perception. The three main points to consistently follow are:

- Be more specific

- Communicate well

- Avoid annoying the consumer

What factors make the biggest impact on consumer choice?

To attract a decent number (more than 10% of the market), there are two main impactful criteria: either a close connection to nature, i.e., free range eggs, or a close connection to the local region, e.g., zero kilometers. This gives a clear and meaningful message to the consumer. It is immediate, simple, and easy to digest. Often, sustainable measures are too abstract and overwhelming with many definitions and options.

What should be communicated before vs. after the purchase decision?

If a hotel pursues a sustainable strategy, it has to be very selective about what is communicated before the purchase decision, since only the above 2 points really increase consumers’ willingness to pay. e.g., Migros supermarket sells sustainable bananas without specifying how they are sustainable. By not delivering the information about the two key values, their success rate is not optimized.